as a fan of craft brews, and living less than 10 miles from one of the most popular microbreweries in the state, I’ve taken a brewery tour or two (or dozen) over the years. from DIY affairs, to ones where the brewmaster takes you back among the tanks to explain the finer scientific points of beer brewing, to very limited, controlled situations where the script never deviates from the one all “tour guides” are compelled to memorize, the experience at the Guinness Storehouse is just that — an Experience.

with annual sales topping more than 1.8 billion U.S. pints, it shouldn’t have surprised me how thoroughly and expertly produced the “tour” at St. James’ might prove. in the dozen years since the Storehouse opened as a self-guided tour and attraction, over four million people have visited. the site, St. James’ Gate, was initially leased to Arthur Guinness in 1759 for the amount of 45 GBP each year for the duration of 9,000-year lease. (the company has since expanded outside its initial footprint and ultimately bought the land outright. a copy of that original lease is displayed under glass in the floor of the atrium.

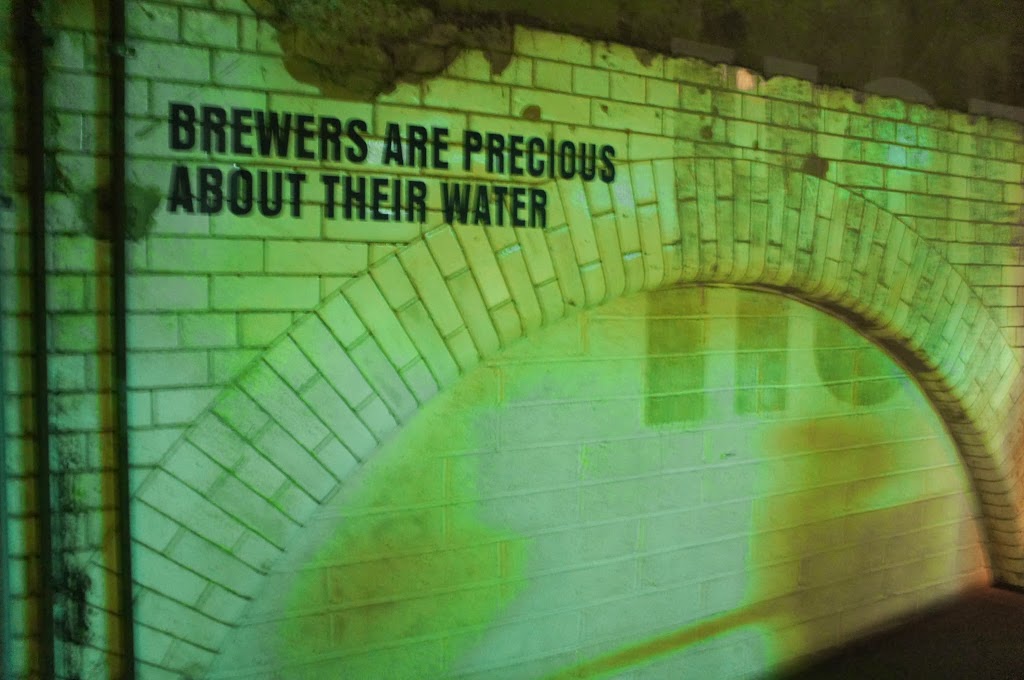

the building that houses the Storehouse was constructed in 1902 as a fermentation plant for the brewery. it served as this capacity until a new fermentation plant was built along the River Liffey in 1988. the attraction is laid out over seven floors in what was, at the time it was built, the largest steel-framed structure in Ireland. the atrium is rather cornily designed to resemble the shape of a pint glass. the first floor introduces visitors to the four ingredients of beer – water, barley, hops, and yeast — and the general brewing process. after years of intimate and in-depth tours of craft and microbreweries, the polish of production surprised me a bit with projections of boiling tubs of wort and ovens of roasting barley, but seemed expertly and deftly done. you can’t actually see Guinness being brewed anywhere along the tour, but you can see the buildings at which various steps of the process take place! on the whole, the exhibits presenting other information interested us more. we saw examples of their famous marketing campaigns – My goodness! My Guinness! – Guinness advertisements on television throughout the decades (with cheesily appointed rooms identifiable by decade), the famous harp seen in the logo encased in glass at the top of one escalator.

the most interesting part, by a stretch, however, was the exhibit on the cooperage. at the height of barrel production (for transporting the black stuff) in the 20th century, Guinness employed hundreds of coopers. within a few decades, as aluminum kegs came into use after 1946, the number dropped precipitously — from some 300 in the war years to 70 in 1961. the last wooden cask was filled at St. James’ Gate in 1963. the exhibit featured all the tools of the trade, as well as fascinating footage from the 1930s or so of men at work – clearly decked out in their Sunday best to show off their work to the camera – working through the entire process of making a barrel. after that exhibit it was mostly down to figuring out where we’d like to enjoy our “complimentary” pint of Guinness. (we opted for the Gravity Bar at the top of the “pint glass” with panoramic views of the city.)

I had absolutely no idea of this: according to Wikipedia, St. James’ Gate traditionally served as the starting point for Irish peregrinos heading to Santiago de Compostela. they could get their credencials stamped in the brewery before catching a boat to Spain; the nearby church will still stamp them for you.