Waikato River is the longest river in New Zealand, running some 425 kilometers from Lake Taupo to the Tasman Sea just south of Auckland. the river is fed from as several streams on the side of Mount Ruapehu and Mangatoetoenui glacier on the mountainside, which are referred to as the Tongariro River prior to feeding into Lake Taupo. at the northeast side of the lake, the wide, meandering river wends its way past the town before funneling into a narrow canyon some 15 meters across, which is carved out of sediment laid down during the Oruanui eruption some 26,500 years ago. that eruption completely changed the landscape of the North Island, coating most of the land with tephra up to 200 meters deep, creating Lake Taupo, and changing the course of what is now the Waikato River from flowing northwest (towards the Pacific) to flowing northeast (towards the Tasman Sea). since the river settled on its northeasterly course, the canyon and falls have grown deeper and more forceful; some 200,000 liters of water tumble over the falls per second. the canyon is some 10 meters deep and the drop over the falls isn’t very dramatic, but the force of the water causes it to shoot out from the end of the canyon to the awe of thousands of visitors (including us!) each year.

Waikato River is the longest river in New Zealand, running some 425 kilometers from Lake Taupo to the Tasman Sea just south of Auckland. the river is fed from as several streams on the side of Mount Ruapehu and Mangatoetoenui glacier on the mountainside, which are referred to as the Tongariro River prior to feeding into Lake Taupo. at the northeast side of the lake, the wide, meandering river wends its way past the town before funneling into a narrow canyon some 15 meters across, which is carved out of sediment laid down during the Oruanui eruption some 26,500 years ago. that eruption completely changed the landscape of the North Island, coating most of the land with tephra up to 200 meters deep, creating Lake Taupo, and changing the course of what is now the Waikato River from flowing northwest (towards the Pacific) to flowing northeast (towards the Tasman Sea). since the river settled on its northeasterly course, the canyon and falls have grown deeper and more forceful; some 200,000 liters of water tumble over the falls per second. the canyon is some 10 meters deep and the drop over the falls isn’t very dramatic, but the force of the water causes it to shoot out from the end of the canyon to the awe of thousands of visitors (including us!) each year.

Tag: river

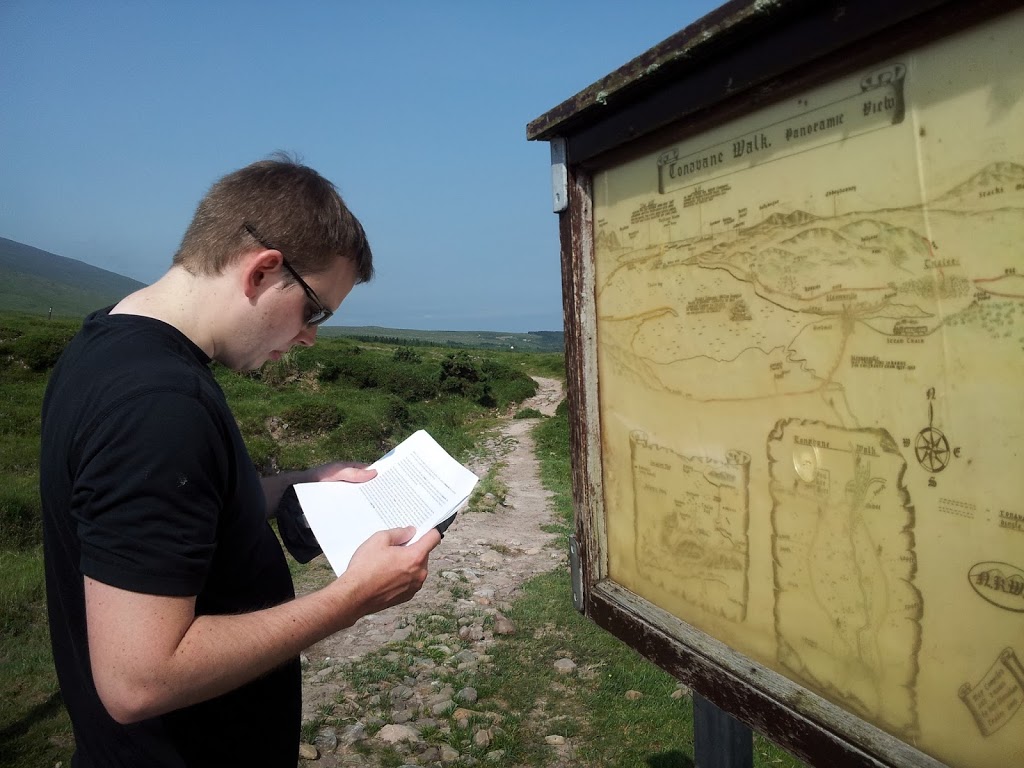

finding the Dingle Way

first day on the trail brought us lots to see and lots to photograph. the path follows a towpath out of Tralee and into the village of Blennerville, whose claim to fame is a functioning windmill that also serves as point of tourist interest, thanks to the Tralee Urban Council, who procured it in 1981.

first day on the trail brought us lots to see and lots to photograph. the path follows a towpath out of Tralee and into the village of Blennerville, whose claim to fame is a functioning windmill that also serves as point of tourist interest, thanks to the Tralee Urban Council, who procured it in 1981.

after passing through Blennerville — and the last shop (for procuring useful goods such as sports drink, chocolate, or peanuts) we saw for several days — we headed up onto the shoulder of the Slieve Mish Mountains. one of the peaks we passed, Caherconree, is named for a stone ring fort found two-thirds up the peak and overlooking the “road of stones.” myth claims the Cú Roí mac Dáire, a one-time king in Muenster rumored to possess magical powers, was able to raise the stones of the for up at night and spin it around so that enemies could not find the entrance. in another myth, a woman held captive in the fort by Cú Roí signaled her rescuer by pouring milk into a stream. that stream that originates near the ring fort is now known as the Finglas, a name derived from a word meaning “the white stream.”

the day stayed cloudy enough to be pleasant without a hint of rain (as it remained throughout the entire hike). the guide pages upon which we relied routinely cautioned how mucky various parts of the track could become given a bit of rain, and it was easy to identify those sections and give thanks that we hadn’t faced that challenge. we saw an assortment of all the livestock we’d see elsewhere along the hike — cows, sheep, horses — though some of the terrain was restricted from grazing. at one point we encountered a herd of brown and black cows grazing directly on top of a crossroads through which we were directed to proceed. we opted to tramp off over the boggy ground rather than get too close to an unknown herd of mothers and their calves. once past the mucky bit we had our first encounter with the biting flies and humid closeness of hedgerows we’d come to know so well. then down over the Finglas river and up into Camp for a much anticipated sit.

the day stayed cloudy enough to be pleasant without a hint of rain (as it remained throughout the entire hike). the guide pages upon which we relied routinely cautioned how mucky various parts of the track could become given a bit of rain, and it was easy to identify those sections and give thanks that we hadn’t faced that challenge. we saw an assortment of all the livestock we’d see elsewhere along the hike — cows, sheep, horses — though some of the terrain was restricted from grazing. at one point we encountered a herd of brown and black cows grazing directly on top of a crossroads through which we were directed to proceed. we opted to tramp off over the boggy ground rather than get too close to an unknown herd of mothers and their calves. once past the mucky bit we had our first encounter with the biting flies and humid closeness of hedgerows we’d come to know so well. then down over the Finglas river and up into Camp for a much anticipated sit.

the ever-changing Camino

there isn’t much to say about Arzúa or our thirty-third day on the Camino. evidence suggests the town was heavily settled before the arrival of Rome; following the expulsion of the Moors, the people who resettled the area came from the Basque region. it sits in the middle of prime dairy land and we saw warnings for cows crossing the road in many places (as seen below). in recent years, however, increasing tracts of land once used for grazing have been given over to eucalyptus groves, which is harvested and used in furniture and paper production. this proved particularly evident in the hike from Arzúa to Arca. several species were imported from Australia in the 1860s and have proved demanding in the ways of all non-native species — without natural controls, they consume resources local species would otherwise use and suck up copious amounts of water.

there isn’t much to say about Arzúa or our thirty-third day on the Camino. evidence suggests the town was heavily settled before the arrival of Rome; following the expulsion of the Moors, the people who resettled the area came from the Basque region. it sits in the middle of prime dairy land and we saw warnings for cows crossing the road in many places (as seen below). in recent years, however, increasing tracts of land once used for grazing have been given over to eucalyptus groves, which is harvested and used in furniture and paper production. this proved particularly evident in the hike from Arzúa to Arca. several species were imported from Australia in the 1860s and have proved demanding in the ways of all non-native species — without natural controls, they consume resources local species would otherwise use and suck up copious amounts of water. fortunate for the plants forced to compete with the eucalyptus, water is in plentiful supply in Galicia — rain shadow and all. this particular day provided us with deceptively numerous ups and downs, dropping down and climbing out of narrow river valleys and crossing over creeks. outside one shop (perhaps attached to a tiny not-yet-open-for-the-season albergue) we saw one of the more unique pack transportation mechanisms of the Camino: someone had attached their bulging pack to a golf cart. there were lots of places earlier on the Camino where this modification would have been more of a hindrance than a help, but on the well-maintained sendas of Galicia it was probably immensely useful.

fortunate for the plants forced to compete with the eucalyptus, water is in plentiful supply in Galicia — rain shadow and all. this particular day provided us with deceptively numerous ups and downs, dropping down and climbing out of narrow river valleys and crossing over creeks. outside one shop (perhaps attached to a tiny not-yet-open-for-the-season albergue) we saw one of the more unique pack transportation mechanisms of the Camino: someone had attached their bulging pack to a golf cart. there were lots of places earlier on the Camino where this modification would have been more of a hindrance than a help, but on the well-maintained sendas of Galicia it was probably immensely useful.

somewhere earlier on the Camino, when the terrain was still rugged (i.e. before getting into Castilla) we saw a guy with a waist harness that hooked up to a bike-sized trailer with kid-buggy size wheels. unlike the golf cart version, this guy didn’t have to tire his arms out by pulling his stuff behind him; he’d just shifted the weight he carried so it didn’t rest on his shoulders. we saw another, larger cart in a village just outside Astorga. a parent at a cafe saw the cart (painted red with slogans on the sides) and wanted to get a shot of his kid standing atop it. they hoisted the young one up and he let out a wail of dissatisfaction that echoed down the main road.

Portomarin

what I remember best from Portomarin is the group of Spanish gents at the table next to us at our dinner in perfect weather under the colonnades singing a Camino-based drinking song. they asked us to take their picture and were all wearing close-but-not-quite-matching hiking gear. the food was pretty good, if somewhat pricier than what we’d grown accustomed to during the portion of our Camino that occurred prior to Sarria. after so many bland bocadillos “sustaining” me through Castilla and León a tasty Galician soup went a long way towards satisfaction.

as with all the other small towns through which the Camino winds in Galicia, the hike from Sarria to Portomarin wended through hamlets consisting of no more than three or four houses each. one village, in which we stopped for a bite to eat at an albergue with at least three employees, had a registered population of one. more people worked at the cafe adjoining this one albergue than officially lived in the village!

as with all the other small towns through which the Camino winds in Galicia, the hike from Sarria to Portomarin wended through hamlets consisting of no more than three or four houses each. one village, in which we stopped for a bite to eat at an albergue with at least three employees, had a registered population of one. more people worked at the cafe adjoining this one albergue than officially lived in the village!

of course, the most notable thing about this stretch of the Camino was passing 100 kilometer mark; some peregrinos (whom we didn’t recognize from our preceding weeks on the road) stopped to pose with the marker which, because of adjustments to the route, doesn’t actually mark the true distance from Santiago. as with the 0 mile marker in Key West in February, we didn’t feel compelled to stop and get a picture but rather pressed on to the next town, took a pit stop, grabbed a banana, and took a photo of the 99km stone. one benefit of the increased number of peregrinos became apparent just before the 100 km mark; whereas before we might have had to trudge through the shallow water of a inconsequentially-small creek or forge ahead unsteadily on stepping stones, the number and nature of peregrinos heading out from Sarria merited path improvements that separated and raised the pedestrian path from the water.

the bridge crossing the rio Minho has proven crucial to the development of the town since Roman times; it bolstered the importance of the village on the east-west route across northern Spain as well as a waypoint for peregrinos during the height of the Camino in medieval times. its strategic importance meant it was usually garrisoned — and mentioned in nearly every medieval and Renaissance-age itinerary through this part of Spain — and thus a useful stopping point for weary travelers of the Camino. even before Alfonso IX (he who died on his way to Santiago) granted control of the town to his preferred religious order, several hospices tended to the needs of the faithful passing through Portomarin.

the bridge crossing the rio Minho has proven crucial to the development of the town since Roman times; it bolstered the importance of the village on the east-west route across northern Spain as well as a waypoint for peregrinos during the height of the Camino in medieval times. its strategic importance meant it was usually garrisoned — and mentioned in nearly every medieval and Renaissance-age itinerary through this part of Spain — and thus a useful stopping point for weary travelers of the Camino. even before Alfonso IX (he who died on his way to Santiago) granted control of the town to his preferred religious order, several hospices tended to the needs of the faithful passing through Portomarin.

this strategic importance changed drastically in the 19th and 20th centuries as motorized vehicles and the roads on which such things traveled favored the town of Lugo, some 30 kilometers to the north, rather than this historically significant and aquatically-situated town. in the 1950s, the town again came to prominence as location as an important source of hydroelectric power; the new reservoir ultimately drown the old town though important artifacts were removed block by block for reconstruction in the new town at higher elevation. apparently when the reservoir loses depth, either for draining or due to drought, evidence of the old town and its original Roman bridge emerge from the muddy lake bottom.

other interesting facts about Portomarin: while the main roads leading up from the river (and the one that transected the main road and led to the main albergue slightly uphill) contained an array of spiffy, tourist-oriented shops, just a block to either side told a different (though not depressing) story. the main drag, catering to peregrinos and other tourists, were quaintly constructed and clean — the picture with the colonnade looks back towards the river and the direction in which the Camino continues. the Post Office was one of the nicer ones I’d seen (though nearly all were more majestic than the one I usually go to at home, which occupies space designed to house a McDonald’s). walk to the other side of the building, or one block off the neat and clean main drag and you’d find a tractor parked, ready to head home after its owner conducted his (or, perhaps more likely, “her”) business in town.

other interesting facts about Portomarin: while the main roads leading up from the river (and the one that transected the main road and led to the main albergue slightly uphill) contained an array of spiffy, tourist-oriented shops, just a block to either side told a different (though not depressing) story. the main drag, catering to peregrinos and other tourists, were quaintly constructed and clean — the picture with the colonnade looks back towards the river and the direction in which the Camino continues. the Post Office was one of the nicer ones I’d seen (though nearly all were more majestic than the one I usually go to at home, which occupies space designed to house a McDonald’s). walk to the other side of the building, or one block off the neat and clean main drag and you’d find a tractor parked, ready to head home after its owner conducted his (or, perhaps more likely, “her”) business in town.

coming down the hill to Molinaseca

one of the more memorable things about the day coming the Cruz de Ferro after leaving Rabanal was how many more peregrinos there seemed to be than in previous days. the number had been growing, to be sure, since we’d gone through Astorga, but the number struck me on day 25 — perhaps because there were so many new faces, not all of which were welcome additions to the rotation of walking companions.

this last leg quickly became a test of patience when it came to new faces who had yet to grow accustomed to the hardships posed by the Camino (i.e. blisters). one woman we encountered on the descent did.not.stop.talking. the entire climb down to Molinaseca. after following along behind her for about 30 minutes as she regaled her companion with all manner of stories about her children, life, work, anything, I discovered (in having to sit at an adjoining table at the only cafe in town where we stopped for a mid-morning snack) that she’d only know said companion for a matter of hours! the majority of which, presumably, she’d been pouring out her life story heedless of her companions attention or interest (but what do I know, perhaps that “unsuspecting companion” was approaching all manner of peregrinos soliciting life stories and this Canadian woman was happy to oblige [yes, I know she was Canadian. I couldn’t help learning that she was Canadian]).

it was a warm day and the downhill grade was a different, if not entirely welcome, challenge after crossing the mesetas. we passed through two small villages, both hosting albergues and other lodging , though clearly struggling or abandoned outside the immediate radius of those establishments. the buildings were older and wood timbered; the two-story stone buildings lining the through-road in the first village had overhanging second floors, sticking out slightly over the narrow, cobbled road. the second village was much the same; it was an interesting approach and exit — not unlike walking through someones back yard or along the edge of someones property to get into town, which felt different in comparison to all the times we approached via the road into town that has been the road into town since Roman times.

it was a warm day and the downhill grade was a different, if not entirely welcome, challenge after crossing the mesetas. we passed through two small villages, both hosting albergues and other lodging , though clearly struggling or abandoned outside the immediate radius of those establishments. the buildings were older and wood timbered; the two-story stone buildings lining the through-road in the first village had overhanging second floors, sticking out slightly over the narrow, cobbled road. the second village was much the same; it was an interesting approach and exit — not unlike walking through someones back yard or along the edge of someones property to get into town, which felt different in comparison to all the times we approached via the road into town that has been the road into town since Roman times.

as a counterpoint to Rabanal, Molinaseca also served as an important point along the trail of Roman gold. the town sits at the base of a gorge created by the rio Meruelo. as we crossed over the river on one of the two remaining medieval bridges, we saw a pair of women — obviously peregrinos, probably much newer to the Camino than us — wading in the water. previously we’d heard cautions against wading in water with which you weren’t familiar; with all the potential infection sites peregrinos might develop on their feet, seemed like sound advice no matter how refreshing a wade in a cool mountain-fed stream might sound.

as a counterpoint to Rabanal, Molinaseca also served as an important point along the trail of Roman gold. the town sits at the base of a gorge created by the rio Meruelo. as we crossed over the river on one of the two remaining medieval bridges, we saw a pair of women — obviously peregrinos, probably much newer to the Camino than us — wading in the water. previously we’d heard cautions against wading in water with which you weren’t familiar; with all the potential infection sites peregrinos might develop on their feet, seemed like sound advice no matter how refreshing a wade in a cool mountain-fed stream might sound.

by the 13th century, the town had transferred from the control of one monastery to another, and the latter granted a charter that provided favorable business terms for Frankish businessmen who catered in large part to the peregrinos heading into the last leg of their Camino. a number of structures dating from this period remain today, and the main street (down which we walked, from the river to the outskirts of town where our more modern hotel stood) was lined by two-story buildings in various states of restoration or disrepair. some rented out rooms, some contained narrow, packed shops, and a couple housed the first wine caves we encountered in the Bierzo region. not your typical tourist-friendly rooms like those you’d see in Napa, the Hunter Valley, or anywhere else known for its wine tasting …

in all, Molinaseca was a nice place to rest, rather than pushing on; true, spending the night in Ponferrada might have granted us an opportunity to visit the Castillo de los Templarios, but Molinaseca provided us with wonderfully comfortable beds, a chat with the Australian couple we’d met back in San Martin, “dinner” with a blue-eyed gray cat, and the opportunity to exercise a civic duty …

the other Mighty Miss

I might preface this post by letting you know that Dave told us we could see the Black Hills from this I-90 rest stop overlooking the Missouri River and Chamberlain. but don’t hold that against me.

on the drive from Sioux Falls to the Black Hills, we stopped at a rest area that overlooks Chamberlain and the Missouri River and boasts a decent interpretive exhibit on the Lewis & Clark expeditions. growing up with more intimate knowledge of both the Wisconsin & Mississippi Rivers (not to mention many, many smaller rivers throughout Wisconsin), I didn’t know much about the Missouri before Dave enlightened us. the other Mighty Miss officially flows some 2,341 miles and, by virtue of being mapped second, is a “tributary” to the Great Muddy. it’s the longest in North America, but only the 13th by discharge and spans 10 states and 2 Canadian provinces. according to Dave, however, the volume of water flowing from the Missouri into the Mississippi lends credence to the argument that the latter is actually a tributary of the former, rather than how matters currently stand. some of the natural length of the Missouri has been cut as meanders were circumvented to make the river more navigable. at Chamberlain, where we saw it, the river was dammed but doesn’t bulk up the river much in terms of width.

on the drive from Sioux Falls to the Black Hills, we stopped at a rest area that overlooks Chamberlain and the Missouri River and boasts a decent interpretive exhibit on the Lewis & Clark expeditions. growing up with more intimate knowledge of both the Wisconsin & Mississippi Rivers (not to mention many, many smaller rivers throughout Wisconsin), I didn’t know much about the Missouri before Dave enlightened us. the other Mighty Miss officially flows some 2,341 miles and, by virtue of being mapped second, is a “tributary” to the Great Muddy. it’s the longest in North America, but only the 13th by discharge and spans 10 states and 2 Canadian provinces. according to Dave, however, the volume of water flowing from the Missouri into the Mississippi lends credence to the argument that the latter is actually a tributary of the former, rather than how matters currently stand. some of the natural length of the Missouri has been cut as meanders were circumvented to make the river more navigable. at Chamberlain, where we saw it, the river was dammed but doesn’t bulk up the river much in terms of width.

while the Lewis & Clark exhibit was informative, it wasn’t anything that tripped my fancy. mostly I remember the keel of a replica boat sticking half-way out the second floor of the rest area, providing a view of the River and a sense of how small the boat was for 20 or 30 men traveling together during this stretch of river.

kayaking the Vltava

another incalculable upside to visiting Krumlov in late September? even in the absolutely perfect weather, I had the whole Vltava River to myself.

because of the town’s location in a crook of the Vltava river, water sports (along with all other manner of outdoor activity — I told you, the Czech enjoy the outdoors) are quite popular and several companies offer kayak and canoe rentals. both my guidebooks recommended getting out on the water, so on my (unanticipated) third day in Krumlov I tracked down one that rented single kayaks.

|

| looking back at the Vltava from the direction I came |

I showed up just as the shop opened and, upon hearing that I — a single person — wanted to rent a single kayak received a dubious look that could have wilted fresh flowers. “You know,” the rental guy said, “it really is better to have someone to go with you, take a two-person kayak.” I am not generally one to get legitimately offended by anyone, but the incredulity with which this guy infused his words struck me. I have kayaked, I have canoed, I have dealt with mild rapids and know how to handle myself. so I told him as much and made it clear that I intended to go no matter what he might think.

so I did (though not until a couple of hours later, when they brought boats into town from the boathouse). I passed sites along the river that, during the high season, offer refreshment (beer) and camping; late September, though, they were all closed. the water was calm and mostly quite shallow. I encountered a few rough patches, had to portage around the weir in town and battled a tendency to turn myself backwards from overcompensating my strokes; but on the whole my biggest concern stemmed from the fact that neoprene does have a saturation point and, upon reaching that point, water leaked through the skirt and soaked through my pants. good thing I opted for my quick-drying pants rather than jeans and against taking the option to bike back to town from the pick-up point in Zlata Koruna.

Krumlov under water

Krumlov has much to recommend it, in spite of the tour bus groups that inundate the town and clog streets, bridges, and every nook of the old town. both the castle and the old town are UNESCO World Heritage sites and, because of the proximity to both Prague and Vienna, it is a highly popular day trip well into the fall. I can’t imagine what the town looks like mid-day in August! even in late September I had gaggles of pensioners, couples, and other tourists to contend with around every corner.

the town sits in a bend of the Vltava River; or rather, it straddles a switchback-like ‘S’ curve, with the Castle perched on a hill at one end overlooking the town center on a near-island below. this location made for an exceptional defensive position in the age of knights and castles, but not necessarily so great in the modern era when the town relies heavily on tourism that the vagaries of nature can disrupt. in August of 2002, the Vltava River flooded badly, submerging much of the historical section of town. (check out photos of the flooding here.) the Lazebnický most was completely submerged (the bridge in the picture), though the railings were removed in time to prevent worse damage from occurring. though the flooding certainly took its toll, the town seems to be doing just fine these days.

new image …

the new banner image is of the monk’s fishing hut in Cong. there’s a trapdoor in the floor of the hut, so they could just drop their nets through the hole and haul up fish.

Gavins Point Dam

on my most recent trip to Sioux Falls, our driving adventures took us out to Lewis & Clark State Park, situated on the banks of the Lewis & Clark Lake, created by the Gavins Point Dam spanning the Missouri River. it’s kind of cool to go someplace that’s so obviously a summer-tourist-weekend-bonanza in the off season. no competition for parking, no dodging small children, no fighting off boat launchers for access to the jetty or to pose as Lewis & Clark on the launch docks.

although on our impromptu jaunt to the west of Yankton was aimed primarily at checking out the park, I managed to convince Becca to take a right along Crest Road that we might investigate the concrete structure on the south end. in a matter of minutes, we were back in Nebraska (again), crossing over the Gavins Point Dam. the hydroelectric dam that impounds Lewis & Clark Lake was constructed between 1954 and 1957 and was authorized as part of the 1944 Pick-Sloan Plan, aimed at conservation, control and use of water resources along the Missouri River Basin. it’s one of six dams on the Missouri River and (according to the US Army Corps of Engineers who maintains the site) produces electricity for some 65,000 people annually.

maybe a tour of the facility would have introduced me to the finer and/or more impressive points of the Gavins Point Dam (but as they’re only open Memorial-Labor Day …); maybe the sight is more awe-inspiring with water flowing over the dam; maybe sunlight glinting off the surface of the lake illuminates this architectural feat of utilitarianism in a mystical way; or maybe I’ll forever be underwhelmed by dams after staring down the slope of Hoover Dam. whatever the reason, I wouldn’t go out of my way to see the Gavins Point Dam again. especially not in the height of tourist season — it goes down to one lane as you pass the generator facility and I have no interest in sitting in that waiting line.

maybe a tour of the facility would have introduced me to the finer and/or more impressive points of the Gavins Point Dam (but as they’re only open Memorial-Labor Day …); maybe the sight is more awe-inspiring with water flowing over the dam; maybe sunlight glinting off the surface of the lake illuminates this architectural feat of utilitarianism in a mystical way; or maybe I’ll forever be underwhelmed by dams after staring down the slope of Hoover Dam. whatever the reason, I wouldn’t go out of my way to see the Gavins Point Dam again. especially not in the height of tourist season — it goes down to one lane as you pass the generator facility and I have no interest in sitting in that waiting line.